Disclaimer: the image for this article isn’t mine and doesn’t hold a lot of baring on content in this post. Though indirectly one could argue it holds a great deal of relevance, but that’s perhaps for another post and another time. Mostly, I just wanted to get your attention, and the image was open sourced to be used for whatever so there ya go. 🙂

I read this article and I decided that I wanted to share it. (I’ve pasted it below in case the article is not published permanently elsewhere.) Mainly I share it because I found the article honest, informative and absent of having “too much” bias. Not that it doesn’t have any, I’m sure it does, but not in a way that is overly obvious or throws anyone under the bus unfairly. I suppose if anyone is the “bad guy” in this article it would be corporations, but I like that no one specific corporation is really being unfairly targeted, it’s more about where we are as a country and society today and how the economic and capitalistic shifts that have taken place have impacted Americans.

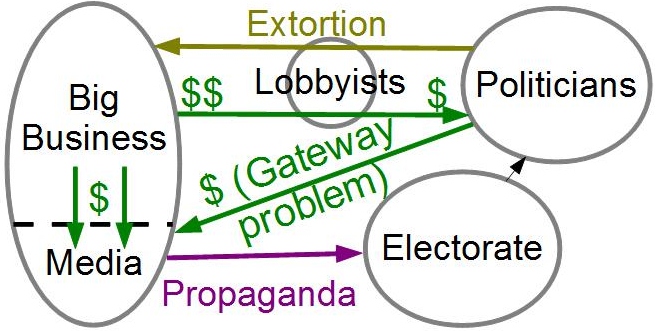

I don’t want to rail on corporations, I’m not “anti-capitalistic” nor am I “anti-corporations” but I will say this, our economic system is broken and there are serious issues of corruption and malpractice within that system. And so the way to fixing that, I believe, is in addressing those things, standing for what is right and supporting the drivers of positive changes that can fix what’s broken.

I think we as Christians (and if you’re not Christian then switch that to we as people) need to take the time to examine what is going on around us and ask ourselves, “is this the best approach to a complete life for ourselves and those around us?” A life that produces a fair amount of our needed provisions through the effort of our employed (or perhaps self-employed) work along with a modicum of lets call it “niceties”. By niceties I don’t mean things, although certainly some “things” might fall under this, ie: a stable place to live, clothes, food etc… But really I mean time; like the opportunity to spend time in activities that are enjoyable and meaningful to ones life, time with friends or family, time reading a good book, time listening to music, time exchanging ideas and stories with a hobby group, time helping loved ones solve some of life’s challenges… Time for life, without the weight and stress of wondering if there will be enough money at the end of the month to pay all the bills, the mortgage/rent, buy food and afford the rest of this worlds cost of living norms.

I guess the notion may sound a little “pie in the sky” but, nothing is impossible with God…right? And going back to the “we as Christians” thing, shouldn’t we be expecting the very best of what life can be? Shouldn’t we be doing our best to know, experience, understand and put into practice those plans and ways of operating in this world that will truly bless… everyone? I think in part for us to do that we need to see and understand what models have outgrown the proper order in accomplishing that kind of prosperity, and take on new ways to effectively do and grow communities, organizations and businesses.

I certainly don’t have all the answers, but I know there are answers and I think if we’re paying attention those answers will be revealed and if we’re willing to change, those answers and changes will see a positive net outcome for the people it touches.

Stepping back to the article I think it does a nice job of examining these things and pointing toward some ideas of changes that we should be wanting and working towards. Just a little piece of information to ponder in moving towards the big picture of God’s great plan for us all.

Hope you enjoy.

The fading American dream? Maybe companies deserve more of the blame.

Late last year, I read an article that wouldn’t leave my mind.

The New York Times reported on a study by Stanford professor Raj Chetty and his colleagues that showed that only 50 percent of those born in 1980 would make more than their parents, jeopardizing a fundamental building block of the American dream: the notion that everyone has the chance to fare better than those that came before them.

Upward mobility used to feel like a sure thing; children born in 1940 had a 92 percent likelihood of out-earning their parents. But Chetty had found that it was going to be increasingly difficult to climb the economic ladder.

In reporting across the country for LinkedIn’s new “Work in Progress” series, people tell me that they feel anxious. In grocery stores, gas stations, doctor’s offices and corporate headquarters, the conversations drift to a familiar place: that the American dream, while certainly not dead, feels harder to grasp.

The factors fueling this sentiment are complex, from globalization to automation and inequality. A smart new book, though, adds another dimension to the discussion, focusing on companies and the erosion of their relationships with workers.

“The End of Loyalty: The Rise and Fall of Good Jobs in America,” by longtime business journalist Rick Wartzman, centers on four iconic companies — General Motors, General Electric, Kodak and Coca-Cola — and offers a fascinating look at the shifts in U.S. corporations since World War II.

Kodak proved instrumental in the formation of 401(k) plans and, in turn, the death of pensions, for example. GM, once the largest employer in America and a road to the middle class for thousands, later paved the way for companies to cut retiree health benefits through a pivotal case in the late ’90s. And while the companies’ financial performances varied — with Kodak and GM both entering bankruptcy at different points — their workers largely ended up in the same place.

Job security deteriorated. Pay flattened. Health and retirement benefits got worse.

“For workers, the American corporation used to act as a shock absorber. Now, it’s a rollercoaster,” Wartzman writes in “The End of Loyalty.”

Today, companies still matter deeply to an individual’s wellbeing. The reality, as the preface notes, is that “most Americans’ fortunes depend directly on whether they have work and how their company treats them, not on the maneuverings of government.”

I talked with Wartzman about how we got to this point — and what changes might help workers in the future. Our conversation, condensed and edited for clarity:

What struck me in reading your book is that the idea of a good job — high pay, some stability, a chance to do meaningful work — is the same now as it was in the 1940s, the decade your book begins.

That’s right. Fundamentally, I don’t think human beings’ basic wants and desires change much over time. You could probably pull a lot of the same things if you went back to the Bible and looked at what people valued in work then: the ability to make a living and live a decent life and then to find real dignity and fulfillment and purpose.

But there used to be a bond between employers and employees — almost a feeling of obligation, you write, among companies to create benefits and a higher standard of living for their workers. When did that start to shift?

Coming out of WWII, there were really ripe conditions to create a strong social contract between employer and employee in America. America’s global competition had been, essentially, bombed out of existence or to its knees anyway. And American companies were truly dominant on the global stage at that point. They could afford to be very generous with their workers.

Another thing is you had all these returning servicemen and, originally, there was great fear that, with tens of millions of soldiers and sailors and airmen coming home, that there might not be enough jobs for them and it might lead to another Great Depression. But, in fact, they would find employment and lead to the birth of this great consumer class in America, right? This was all fueled by companies’ generosity in putting lots of high wages and good benefits into their workers’ pockets so it became this virtuous cycle.

Another factor in terms of ripe conditions was this was a period when unions had great strength. So it was in the ’50s that we saw union private sector union membership at its height in America. And what’s significant is that this collective bargaining, this collective voice and power that workers had — a countervailing power to corporate power — was something that had a tremendous spillover effect across the economy.

And it seems like you need to be at about 25 percent to 30 percent plus of the private sector workforce being unionized to have that kind of spillover effect. We’re at less than 7 percent of the private sector workforce unionized today. And I think it’s one among many reasons that the social contract is not as strong as it was.

Right, so when do we start to see this change?

You could really see it by the early ’70s and, particularly, after the recession of 1973 and that really exposed some weaknesses that had developed across the economy. This was a period, as many of your readers will recall, of not only high unemployment but also a tremendous inflation. So you had this one-two punch known as stagflation. And it was awful until the Fed really broke the back of inflation in the ’80s.

For workers, you began to see increasing effects of automation. You began to see the effects of the decline of the unions. There was a tremendous shift now underway from a blue-collar economy, where people who are able to really reach the middle class and find a good job, at least, in terms of the hard side of the social contract: good compensation, pay, benefits, job security and retirement — all of those things that came through their employer. You began to see the shift to knowledge work where, if you didn’t have skills and education, you couldn’t find those kind of good jobs anymore. And so for those who do have skills and education, they’re the winners in this new economy, which has only accelerated over the last 30, 40 years. And their cousin are kind of low-end service workers who really, really struggle to make ends meet.

The other really important trend that has greatly, greatly amplified all the forces that I described is one that came a little bit later — really through the ’80s and accelerated into the ’90s and where we are today — and that is this preoccupation among most big corporations, at least the publicly traded ones, with maximizing shareholder value. This has been, to me, the gasoline on all those other sparks. It has just really, really put workers, very explicitly, in second place. It was in the golden age, in the post-war period, when corporate CEOs talked, very explicitly, about their need and their responsibility to serve all stakeholders: so not only shareholders, but their customers, the communities they operated in, and their workers. They talked about balancing all of these interests. Once you make shareholder primacy the new ethic and you explicitly elevate shareholders above all those other stakeholder groups, they by definition lose. Workers have lost a lot.

So, if shareholders are the ones corporate executives are most focused on, is there ever a world where that isn’t true? It would seem tough to change that dynamic.

I think it’s going to be very hard to shift. It’s a huge force. Also, there’s something beautifully and breathtakingly simple about it all. We can keep score easily. How are we doing? Well, let’s look at our share price. We can look at it second by second if we want to. It’s a very simple thing; whereas, how do you measure how well you’re doing for all your stakeholders? It is possible to measure, but again, it’s a balance and it’s trickier and it’s just not as clean or easy. That’s one appeal of the shareholder model.

Another appeal, and I think the largest driving appeal for many companies, is that CEO pay has become very explicitly linked to rising share price. Anywhere from 50 percent to 80 percent — depending on which studies you look at — of big company CEO compensation is now tied to share price and often in the form of stock options and often to relatively short-term share price. It’s not in their interest to change back to a stakeholder model.

But all that said, I think there is growing recognition that that system has led to short-termism that’s had bad effects on workers and others and companies not investing in their workers with higher compensation, giving labor a bigger share of a very large profit pie. Corporate profits have been near record highs in recent years. Workers just aren’t sharing in the gains as they once did.

There are some pushing back. A number of companies, hundreds, have stopped giving quarterly earnings guidance, because CEOs and boards don’t want to feel under the tyranny of this kind of pressure from Wall Street. You have companies like Unilever and Paul Polman, the CEO there, who has very explicitly denounced this shareholder primacy model and very openly embraces a stakeholder model. There are others, but they are the exception, and it’s going to take a lot of forces, I think, to move that back.

Let’s talk about the nation’s largest private employer today: Walmart. While you were business editor at the Los Angeles Times, you helped shape a series on Walmart’s effect on the economy that later won a Pulitzer Prize. If we’re talking about good jobs and what companies can do, how do you rate Walmart today?

I think they’re a company that actually deserves credit for starting to understand that you have to put more compensation into people’s pockets for them to just not have so much stress in their lives; that it’s very hard to come to work and do a good job each day. I commend them for raising wages. I think it went from whatever it was—10 bucks an hour—up to like $13 or something.

Right, now the average wage is about $13.25 for hourly full-time employees; part-time employees make about $10.50.

They also have this immense training program. I think as many as, what, like 225,000 people in some kind of front line to central management sort of training, right?

Yes.

Which is wonderful, and again should be commended. Most companies are not doing that. They’re not investing in their people in that way. There’s some interesting numbers from [management professor] Peter Cappelli at Wharton, who found even in the late ’70s that the typical worker was getting two and a half weeks of skills training a year from that company, and now that’s down to 11 days. Most get nothing at all. It’s just a huge shift, so again you would applaud Walmart, it’s great. All of that said, there are many, and I would put myself included, who think that Walmart can do even better on the wage front. It varies from location to location whether you’re in a rural place or whatever, but I would like to see all of their workers make truly a living wage, and I don’t believe they’re at that level yet.

So, let’s go back to this idea of good jobs. What other reforms would you like to see to make work better for professionals today?

First of all I should say: I don’t think we’re going to go back to a time of a post-war golden age where we just have this tremendous rise of the middle class and this period of by and large just greatly shared prosperity.

We as a society, we as the business community, as business leaders, we have a choice to make. We can say: Man, there’s so many pressures now that we’re just going to sort of hunker down and act in our own self-interest. But what we’re going to say: We are facing all these pressures and we have a responsibility to make sure that in the face of all these pressures we actually try and do more. And we may not be able to get all the way back to where we were but we actually have more than an obligation to try and help those who feel left behind.

Again I don’t think we’re going back, but to at least move in another direction. There’s a Peter Drucker quote that I use at the end of the book, which I think is a tremendously great observation: “A healthy business cannot exist in a sick society.” I think that there’s just got to be growing recognition and I think there is in some ways, growing recognition.

I was just talking with Alan Murray from Fortune.

Right, Alan Murray, the chief content officer of Time Inc.

Alan, who I respect tremendously — he was my former boss at the Wall Street Journal and colleague there and a friend — started this Change the World list, and he’s got this new CEO initiative that he started, which follows in the wake of this gathering of Fortune 500 leaders at the Vatican last year, to talk about all these issues.

And his strong sense is that it’s not the majority but more and more CEOs are waking up to this fact that their business is not going to sustain itself. Business will not sustain itself. Capitalism may not sustain itself.

If more and more people feel like the system’s rigged, they’re left behind, there’s no way for them to advance, they don’t see a path to a better life for them or their kids, and that’s just unsustainable.

And so, his feeling is that more and more business leaders are slowly starting to recognize this and starting to step up and begin to at least think about: What is our role and responsibility? And I’m heartened by that although I don’t wanna be too Pollyannish but hope it is the beginning of something.

The last thing I’d say is that I think all of us — that is, regular people — can help push on that trend by acting in our capacity as employees.

Can that have a bearing on the future? Absolutely. There’s going to be maybe a shortage of talent as Baby Boomers retire. Companies are going to have to woo these workers; they better behave right and do it authentically.

That’s an optimistic view. I talk to people across the country and they say that the American dream feels harder to achieve. Do you feel that companies can play a role in restoring this dream? Can there be a shift so people don’t feel left behind?

People will stop feeling left behind when they’re not left behind as much. If companies can start to pay more and start to ensure that their workers have the training that they need, then people will start to believe again more.

It’s not coincidental that those were the things going on when this notion of the American dream seemed so much more alive and vivid and people had confidence in the future. Those things go hand and hand.

There is a huge role for government in all this, obviously, and there are things that need to be done in my mind. A true living wage and not just a minimum wage. Expansion of the earned income tax credit, which should really be a no-brainer and bipartisan and something that helped the working poor. The need for portable benefits and new labor standards and protections for independent workers. Again, this is a hugely fast-growing part of the labor force, and depending on how you measure it anywhere from under 10 percent to more than 30 percent of the labor force, right?

The truth is the government, while hugely important, sets the guardrails and it provides the ultimate safety net, but companies are the main players. Business leaders are the main players here and they’re the ones making the decisions that really affect people’s lives day-to-day and so I feel like there’s a huge measure of responsibility.

They have to do better.

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.